Category Archives: News-and-Updates-TEXT

Packers Assistant Coach Takes On Dyslexia

Packers Assistant Coach Takes On Dyslexia

Packers Assistant Coach Takes On Dyslexia

By Lori Nickel of the Journal Sentinel

Photo by: Mark Hoffman

The night before Joe Whitt Jr. was supposed to get up in front of every Southeastern Conference football and basketball coach and athletic director to give a speech as the student advisory representative, he pulled out his notes.

Reading them, the old anxieties came back.

So he made a bold choice: He would memorize the speech. And toss the notes.

The next day, he got up in front of all those famous, powerful people and hit a home run. He delivered on the key topics, spoke with confidence and authority and was congratulated by the SEC's biggest names for a job well done.

But what they didn't know - what most people didn't know, what even he didn't know for a long time - was that he had to memorize that speech. He was dyslexic, and reading that speech might have just garbled the whole thing up.

"It's a curse. But it's a gift at the same time," said Whitt. "You just have to not be afraid to get help. And then you can flourish from there."

Taking on the challenge

Now, the Green Bay Packers defensive backs coach is still working around the challenges of dyslexia. He has just completed "The 48 Laws of Power" by both reading it and listening to the book on tape.

And now he's reading "The Power of Who" page by page.

"And with my dyslexia, it's hard for me," said Whitt. "It takes me a long time to read a book, to be honest with you. But I fight through it. I'm trying to read as much as I can, because my kids are young and I want them to see Daddy reading."

Whitt has an agenda here, starting with his 6-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter, but reaching further than that, if he can help it. He is a "geek" - as in, the nationwide library campaign that encourages everyone, especially children, to use these carefree summer days to crack open a book and open their worlds.

When Whitt opened up about his dyslexia right before Super Bowl XLV he looked like a good role model for the library campaign, so they contacted him and he agreed to help.

Whitt poses with the Lombardi Trophy and his Super Bowl XLV ring in his home office in Alabama and the photo is displayed in libraries all over his home state: Joe Whitt Jr. "Geeks" Competition.

There was a time when this subject was very painful for him, mostly because he didn't know what it was. He never knew anyone with dyslexia.

"I just knew I was being pulled out of class up until fifth grade," said Whitt. "As a kid I was terrified to be called on in class to read aloud. In the ninth grade, I started telling my teachers - all the way up to my professors in college - don't call on me to read. I'm not going to do it. Because I was just terrified.

"And at the same time, I'm president of the class, now. I made good grades. It's just - I wasn't very good at reading. I had dyslexia."

Father's career

His father, Joe Whitt, is legendary in the SEC and Alabama, a gifted former assistant coach at Auburn who helped the Tigers win five SEC titles and appear in 17 bowl games. He also coached 20 players who were drafted in the NFL. But he probably just worked around his dyslexia, never officially diagnosed, as well, said his son.

As for Joe Whitt Jr.'s son, yes, he looks for signs of it constantly, but only because Whitt wants to make sure he can help his son in every way possible and encourage him to not give up because reading is hard.

You just don't tell a Whitt he can't do something.

"I could care less if my kids play sports," said Whitt. "It's OK if they want to. But what I want is them to be given every chance to be successful through their education."

Memory skills

Whitt believes his dyslexia actually might enhance his memory skills. He was told about a recent development in which research showed some people with dyslexia might have excellent peripheral vision.

To Whitt, that was no surprise at all. For him, his memory is exceptional. He also gave his high school graduation speech from memory, not notes. And he said his dyslexia presents no challenges to him in his role with the Packers.

"I don't read well, but my memory is unbelievable. So, if I hear something? I have it," said Whitt. "It really helps me now because as we're putting in systems and schemes, if it doesn't flow, it doesn't make sense to me. So, I won't let it go until it makes sense to me. Because I know once it makes sense to me, it's going to make sense to my players.

"And I can see that my dad has the same memory that I have. He can give a speech off of memory, just look at a couple of bullet points and go with it."

So there's really two messages here from Whitt, who delighted in seeing Miami Heat superstar LeBron James reading before one of the NBA Finals games.

Helping out

He wants kids to get help if they need it and he wants kids to go to the library and get "geeked" about something.

"I want to get kids to know that it's cool to read," said Whitt. "Right now, especially in the black community, there are too many kids who think the only thing they can do is play football, basketball, or be a rapper or a singer, or an entertainer to make it out of their situation.

"I don't think it's said enough, so I'll say it. I want kids to realize, you can be smart - and still have a learning disability. You have to work around it."

Read more from Journal Sentinel: http://www.jsonline.com/sports/packers/packers-assistant-coach-takes-on-dyslexia-qc63epj-162487386.html#ixzz2kUk02yR6

Follow us: @NewsHub on Twitter

The Dyslexia Educational Network Broadcasting at DyslexiaEd.com

Topics:

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems

Dyslexia Could Never Sack Jets’ Tebow

Dyslexia Could Never Sack Jets' Tebow

Dyslexia Could Never Sack Jets' Tebow

Photo by Bill Kostroun/New York Post

nypost.com

By Brian Costello

CORTLAND — Tim Tebow was 7 years old when his mother Pam had him tested for learning disabilities. Tebow took a few tests to see how he processed information and what his IQ was. The results showed he was dyslexic.

Seventeen years later, Tebow is sitting on the edge of the Jets’ practice field. The quarterback just finished his best practice of training camp as he sat down with The Post to discuss the challenges dyslexia has presented.

“There’s a lot of people that have certain processing disabilities and it has nothing to do with your intelligence, which I think is a big misconception that people have,” Tebow said. “Coach [Rex] Ryan has dyslexia. He’s one of the most intelligent football coaches around. I’ve always tried to share, especially with kids, to be confident with it. You know, ‘hey, this isn’t something that’s a handicap. You just have to learn how you learn and overcome it. It’s something that you can be better off because of, because you know how you learn.’ ’’

Tebow is a kinesthetic learner, meaning he learns by doing rather than by sitting and listening to a lecture. He said he learns best by walking through things, then writing them down.

Some people have theorized that Tebow struggles in practice because he has a tough time learning the playbook. But Tebow said he does not think dyslexia has affected him on the field at all.

Since the Jets acquired him in March from the Broncos, he has spent his time learning offensive coordinator Tony Sparano’s system and feels he has not had a problem.

“This is my third offense in three years, so I feel like I’ve done a pretty decent job in trying to understand each offense and grasp it,” Tebow said. “Who knows? Pretty soon I might have all the offenses.”

Dyslexia runs in Tebow’s family. Both his father Bob and older brother, Robby, are dyslexic, too.

Tebow was home-schooled by his mother, who would quiz Tebow and his siblings at the dinner table. When he got to college at Florida, he found the classes in Gainesville were easier than what his mother threw at him back home.

“My mom was sometimes pretty tough,” Tebow said. “She made me work hard. I think [college] was easier because I was never the best test taker, but I felt like I was pretty good at doing my work and projects and getting things done and everything like that. So, I was very blessed at Florida to graduate with honors and did some pretty good things there.”

Tebow majored in family youth and community sciences with a minor in communication. He wanted to learn about starting his own foundation and become a better public speaker. At Florida, Tebow was permitted an extra 30 minutes to finish exams because of his dyslexia. But he declined the extra time.

“I felt like if I knew it, I knew it,” Tebow said. “If I didn’t, it wasn’t going to come to me. I just felt like I’m going to study hard and have this information down. I didn’t feel like I needed the extra time.”

He graduated with a 3.7 GPA.

Tebow now spends time speaking to children with dyslexia about what he’s been through. Many of the kids feel insecure about the disability.

“When kids get labeled as a dyslexic, they think, ‘oh man, does this make me dumb? Does this make me stupid? Does this make me not as intelligent as this person?’ Absolutely not,” Tebow said.

Kids now see an NFL quarterback, who is one of the most popular figures in the country and who overcame his learning challenge.

“I’ve always looked at it like if I can take this and help kids that might be shy about it or insecure about it,” Tebow said, “or it’s something that affects their self-esteem, then I’m glad I have it.”

The Dyslexia Educational Network Broadcasting at DyslexiaEd.com

Topics:

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems

The Dyslexic Engineer

Dyslexic Engineer

The Dyslexic Engineer

by Paul J Clarke MIET

I found out I was Dyslexic when I started secondary school at the age of 12. By the time I left I had poor grades and was told I would not amount to much. However Dyslexia is not a disability or have something missing in our brains, its just the way we are wired up. So how does someone with dyslexia get by in a world or words and what magic powers have some of us harnessed that has given us an advantage over others, like me in becoming an electronics design engineer.

At the beginning I can remember looking at black boards or pages of text having no idea what other kids around me were seeing. For me the pages may have well as been blank for all I could gleam from them. However I was lucky as when I started my secondary school my teacher spotted what I was having problems. I was tested for Dyslexia and found to have a mild form. The approach for me in my English lesions from my teacher was not to learn to read although that was a part of it, but more to focus on the things that dyslexics and autistic people have, the ability to see things differently. For me I was able to rotate images in my head and look at drawings and describe what could not be seen or how it would look form a different angle. I also found i could memorize chucks of maps, drawings etc in a almost photographic type way. My teacher encouraged these skills and gave me and others more confidence which lead us to start learning to read more and more. By the time I left school at 16 I had reading age of around 10.

Over the years I have slowly got better at reading and writing but its still painfully slow compared to the speed my brain wants to run at. Computers and PCs were just entering homes and when I started my ONC in electronics at collage I know I would have never finished it or my HNC without Word and a spell checker!

Since then I've relied heavily on computers to get by in my working day. Lists are important to me and where I work we have an internal wiki which I use to assemble ideas. Just more recently I have found www.workflowy.com which is a really nice little online tool for generating lists. I have also used a package called Bugzilla which is fab at tracking faults, bug or issues on software projects. Bugzilla however is quite flexible and can be used on hardware projects or even just you day to day life. Being dyslexic meant I had to be better at project managing my day at work - unfortunately I've never quite got it to work at home.!

Another really good tool I use is to block out my calender in Outlook using bright colours. each colour means a different type of task and allows me to look and see quickly what I've got planed. I also block out my whole day, not just for appointments or meeting, but anything I want to get done. This way I don't forget what I have planed and have already set aside time to do it.

Many of these things may look and sound like project management tools. In away I have stolen them from this area of business but you will find that these techniques are being taught to people today with dyslexia. these are methods of giving back Dyslexics some control.

There was recently a program on the BBC called "Don't Call Me Stupid" which follows the UK actress Kara Tointon who explain just what it like to be dyslexic and for anyone who watches it you will also see the emotional impact that it can have on a individual too. For me I forgot just how hard I found it to get though school and now having tools and work arounds I don't get those feelings of depression and frustration anymore.

For me I now find Dyslexia a gift. I do not think I could come up with design ideas and play around with stuff in my head if I was not like this. I now talk around with large chunks of circuits and software in my head that I can think over, try ideas and work stuff out. It’s like having a 3D whiteboard in my head. I still need pen and paper but in a funny way I like being dyslexic. I can get by with the reading and writing and getting my words mixed up, however I think I've come out better off in my career because of the way my head is wired up.

I would say to anyone who is dyslexia not to give up. Many are told that they will never come to much and give up too easy. I have always aspired to be more, maybe because I'm dyslexic,and so should others.

Posted by Paul J Clarke MIET

Topics:

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems

The Paradox of Dyslexia: Slow Reading, Fast Thinking

The Paradox of Dyslexia: Slow Reading, Fast Thinking

MOLLY PATTERSON APRIL 3, 2011 2

Dr. Sally Shaywitz is the Audrey G. Ratner Professor in Learning Development, and Dr. Bennett Shaywitz is the Charles and Helen Schwab Professor in Dyslexia and Learning Development and Chief of Child Neurology at Yale University. Together they head The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, which studies the correlation between reading and IQ in dyslexic and typical students, shedding new light on what has been termed “the hidden disability.”

Dyslexic students are often frustrated or confused as to why certain assignments – reading, for example – take them longer to complete than their peers. “Someone once said to me, ‘I wonder what it feels like when a child first realizes that he or she can’t do what those around him or her are doing.’ And that was really quite devastating,” says Sally Shaywitz.

She and her husband Bennett set out to help these students by examining the science of dyslexia. Most recently, the Shaywitzes at the Yale Center for Creativity & Dyslexia have established a connection between IQ and reading in dyslexic students versus typical students.

Connecting IQ, Cognition, and Behavior

The Shaywitzes conducted epidemiologic longitudinal research on a large sample population of Connecticut students. Twenty-four elementary schools were chosen from the state of Connecticut – two were randomly selected from twelve separate towns across the state – and students were tested upon entry into kindergarten. The same students were tracked over more than twenty years, each taking a reading test annually and an IQ test biannually until adolescence. The tests were individually administered, constituting a statistical “gold standard,” according to Sally Shaywitz. Including these tests, researchers examined the cognition and behavior of dyslexic versus typical students and then recorded and compared the brain images of dyslexic and typical students.

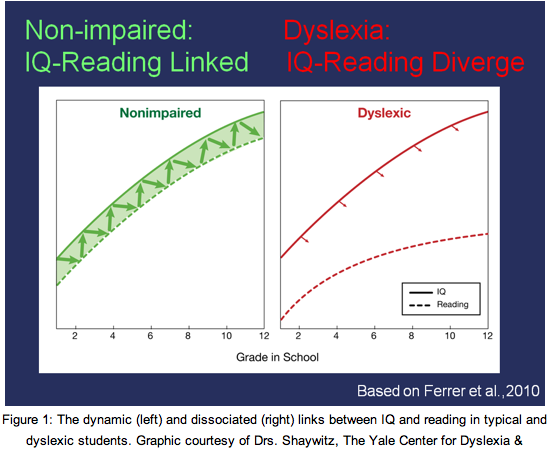

The results show that in typical readers, IQ and reading track together and are dynamically linked over time. Sally Shaywitz calls the two components “kissing cousins” because they are “intertwined,” a conclusion that she notes has been widely accepted by the public. In contrast, the Shaywitzes found that in dyslexic readers, IQ and reading diverge. Thus, a highly intelligent dyslexic student can have a low reading score. This paradox is illustrated in Figure 1, where the left panel shows the dynamic link between reading and IQ development in typical readers, and the right panel shows the disconnection between reading and IQ in dyslexic readers.

figure 1

Figure 1: The dynamic (left) and dissociated (right) links between IQ and reading in typical and dyslexic students. Graphic courtesy of Drs. Shaywitz, The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

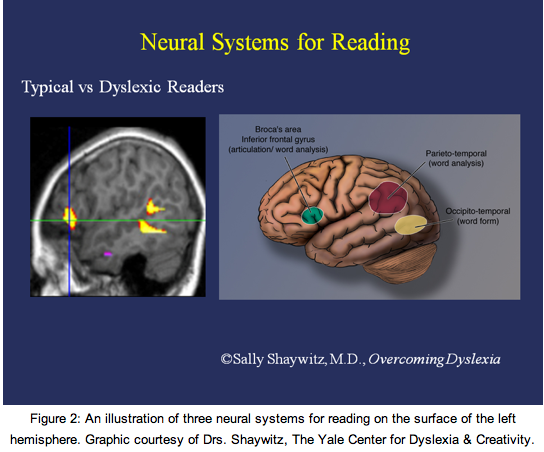

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to record images of dyslexic and typical children and adoslecents. Figure 2 illustrates these images: The left figure is a composite fMRI of 74 typical readers contrasted with 70 dyslexic readers. The yellow regions are parts of the brain that are more active in typical readers com-pared to dyslexic readers. The right figure is a schematic view. Both images show three systems for reading: an anterior system in the region of the inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area), which is believed to serve articulation and word analysis, and two posterior systems, one in the parietotemporal region, which is believed to serve word analysis, and a second in the occipitotemporal region (the word-form area), which is believed to enable the rapid, automatic, fluent identification of words. These systems are used for fast, fluent automatic reading, but the scans show that dyslexic individuals are neurobiologically wired to read slowly.

figure 2

Figure 2: An illustration of three neural systems for reading on the surface of the left hemisphere. Graphic courtesy of Drs. Shaywitz, The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

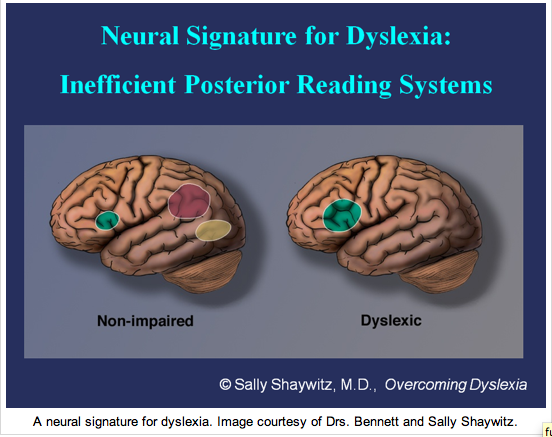

Functional brain imaging has made the once-hidden disability of dyslexia a visible one, increasing awareness and understanding of dyslexia in education and policy-making. As one of many resulting policies in education, dyslexic students are often allotted additional testing time. This allows them to demonstrate what they know and not be penalized for slow reading that is biologically determined and therefore beyond their control. These compelling findings of a neural signature for dyslexia are, according to Bennett Shaywitz, “replicable around the world.”

Dyslexia Around the World

Dyslexia, a fundamental difficulty in separating the sounds of a spoken language, is common to every alphabetic and logographic language. In languages with increased transparency between sounds and letters, including Italian or Finnish, dyslexic children may initially appear to read accurately, with difficulties often not emerging until adolescence or young adulthood. Bennett Shaywitz cites a study by Eraldo Paulesu, who aimed to compare dyslexia in Italian, English, and French college students. He had to recruit Italian college students in schools of engineering because so few Italians had been diagnosed with dyslexia. Indeed, dyslexics not only succeed in engineering but in a range of fields including medicine and law. Ultimately, although they are slower readers, dyslexic students have strengths in higher order thinking and reasoning skills. In fact, as Bennett Shaywitz points out, the 2009 Nobel Laureate in medicine, molecular biologist Dr. Carol Greider, is dyslexic.

The scientific and educational communities have reacted positively to the results of the IQ and reading study, says Sally Shaywitz. The results are particularly compelling because they confirm the relationship between IQ and reading, elucidate the experiences of the dyslexic, and corroborate the clinical findings of other researchers.

As a secondary result of the study, the data identified certain basics of dyslexia that were initially unknown or misunderstood. “From an epidemiologic perspective, we’ve been able to determine from the random sample of Connecticut school children that dyslexia affects one in five individuals,” says Sally Shaywitz. “We’ve also found that there is no significant difference between the number of girls and boys identified [as having dyslexia].”

figure 3

A neural signature for dyslexia. Image courtesy of Drs. Bennett and Sally Shaywitz.

Identifying Dyslexia in School Systems

School systems often have trouble identifying dyslexic students because testing students for dyslexia is not a standard procedure, and dyslexic individuals often exhibit only subtle symptoms. It is often difficult for teachers to recognize that the same child who is extremely bright can also be the one who is struggling to retrieve spoken words or to read fluently.

To better help students with dyslexia, Sally Shaywitz suggests teachers instruct dyslexic students in smaller groups of a size no bigger than five students. Instruction needs to be delivered in this manner consistently – 60 to 90 minutes a day, 4 to 5 days a week – by educators trained in teaching dyslexic students. This is a tall order and “a very slow, laborious process,” Sally Shaywitz concedes, but rewarding in the end. Sally Shaywitz says that accuracy can be taught; however, closing the gap in reading fluency continues to remain an elusive goal.

Looking Ahead: Standardized Testing

The Shaywitzes are focuing new research on how the disparity between IQ and reading in dyslexics affects their performance on high-stakes exams such as the SAT, MCAT, and other standardized tests. Dyslexic students require the accommodation of extra time, which is supported both by scientific evidence and the law; but testing agencies often withhold this accommodation “to the detriment of the student and society,” says Sally Shaywitz. The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity has focused its efforts on determining the “predictive validity” of these tests. Such results may be uneven between dyslexic and typical students, given the heavy emphasis of reading fluency on standardized exams. The data on this new research is not yet available, but will certainly be anticipated by students, educators, and testing companies alike.

About the Author

MOLLY PATTERSON is a sophomore Chemical Engineering major in Trumbull College.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Drs. Sally and Bennett Shaywitz for their time and for their dedication to research.

Further Reading

Ferrer, E., Shaywitz, B.A., Holahan, J.M., Marchione, K., and Shaywitz, S.E. Uncoupling of Reading and IQ Over Time: Empirical Evidence for a Definition of Dyslexia. Psychological Science, 21(1) 93–101, 2010.

Shaywitz, S. Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. 2003. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Bennett A. Shaywitz, Pawel Skudlarski, John M. Holahan, Karen E. Marchione, R. Todd Constable, Robert K. Fulbright, Daniel Zelterman, Cheryl Lacadie and Sally E. Shaywitz, “Age-Related Changes in Reading Systems of Dyslexic Children,” Annals of Neurology, Volume 61, Number 4, (2007): 363 – 370.

Sally E. Shaywitz, Maria Mody and Bennett A. Shaywitz, “Neural Mechanisms in Dyslexia,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Volume 15, Number 6, (2006): 278-281.

Topics:

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems

Can Dyslexics Succeed at School or Only in Life?

Lisa Beizberg

Lisa Beizberg

Founder and Chair Emerita, PENCIL (Public Education Needs Civic Involvement in Learning)

Can Dyslexics Succeed at School or Only in Life?

There's something funny about learning that a successful CEO or politician received bad grades in school. We're amused to hear that Steve Jobs earned C's on his way to a 2.6 GPA in high school-- before creating the most profitable company on Earth. But what if stories like these say more about the quality of our schools than we think? Indeed, statistics show that schools in the United States may not be fostering the skills needed to succeed in life after high school. A shocking number of high school graduates require remediation when they get to college. In New York City - which, unlike most other districts, is tracking the data and attempting to do something about it - more than half of high school graduates aren't prepared for coursework in in community college. Naturally, cities and states (and the authors of the Common Core Standards) have begun adjusting their approach, shifting focus to higher level skills like problem-solving, critical thinking, and even creativity. It's time we took a similar approach to the education of students with learning differences and learning disabilities.

For too long, educating students with disabilities has been treated as a challenge separate from educating students in "mainstream" classrooms; for many casual observers, "special education" brings to mind a population with severe physical and intellectual disabilities. Even the term "special" suggests an entirely different approach is required, not meant for students who can sit still and memorize facts on a smartboard. Indeed, many students with severe disabilities - such as autism or developmental disorders - require special attention, and often separate facilities. But most of the 3 million students with disabilities (out of roughly 54 million students in schools today) are fully capable of being taught in a mainstream classroom, provided our schools are willing to make some changes. Students with learning differences have tremendous talent, creativity, and academic potential--not to mention potential to enhance the learning experience of those around them. That most school systems have failed to recognize this is a regrettable missed opportunity, both for students who learn differently and for their general education peers.

Take dyslexia, for instance. A long list of dyslexics have had remarkable success in their careers, from President Woodrow Wilson, Winston Churchill and General George S. Patton, to Tommy Hilfiger, Steven Spielberg and Richard Branson. A study conducted by Julie Logan, a professor of entrepreneurship at the Cass Business School in London, found that a disproportionately high percentage of American entrepreneurs identified themselves as dyslexic--more than a third of entrepreneurs, compared with ten percent of the overall population who identify as dyslexic.

Why are so many entrepreneurs dyslexic? Perhaps dyslexics are accustomed to being stuck in a system that doesn't nurture or recognize their own skills, so it becomes necessary to think outside the box. Or, perhaps because they have faced adversity from a very young age, dyslexics develop what the expert Paul Tough has termed "grit." As he has written, students who learn to overcome failure and demonstrate resilience and persistence (often in combination with a nurturing family environment) are most successful in school and beyond. In a similar way, my daughter - who is dyslexic - has developed a determination and, yes, grit that I know will come to benefit her after high school. And yet, throughout her life, she continues to be told: "school doesn't work for you, but life certainly will." Now, in her early teens, she's asking, "why can't school work for me, too?"

There's no reason it shouldn't. Dyslexics possess a set of skills that equip them well for what Daniel Pink calls the new "conceptual age." Abilities once thought frivolous, like creativity, empathy, and inventiveness will, Pink writes, "increasingly determine who flourishes and who flounders." These also happen to be skills observed in students with dyslexia. If dyslexic students appear to be adept at thinking outside the box, adapting to new situations, and solving problems - which are key to success in the workplace - our schools ought to reward these skills as opposed to, say, rote memorization and the ability to complete a test in under two hours. Instead, dyslexics are typically consigned to years of adversity in the classroom, stuck in a system where success is often out of reach.

Even the corporate world has figured out that problem-solving skills are a better predictor of success than an employee's performance on standardized tests. Google's partnership with Cornell NYC Tech, a new graduate school to be located on Roosevelt Island, is just one example of businesses making a commitment to help students succeed in a 21st century economy. The same goes for IBM's investment in P-TECH (Pathways in Technology Early College High School), a recently created high school in Brooklyn, where students can earn an associate's degree within six years and a job with IBM. A similar approach can and must be brought to educating students with learning differences.

While schools systems may be avoiding it, many educators across the country are tackling the challenge head on. At the Kildonan School, an all-dyslexia school in upstate New York, one-to-one tutoring sessions tailor instruction to each child's individual needs--allowing students to advance at their own pace, rather than fall behind while the rest of the class moves on. At the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, Dr. Sally Shaywitz leads research on the best ways to help dyslexics draw on their strengths - the creativity, empathy, and critical thinking - to "hit their targets in life." However, accommodations for dyslexia and other learning disabilities are far from the norm.

As is often the case, our children know better. Dr. Diana King, a leading expert on dyslexia for the last 50 years, often asks young students to raise their hands if they would like her to sprinkle magic fairy dust and make their dyslexia disappear. Never more than one hand rises. Our children are eager and ready to meet their potential, not after high school or college or "in life', but at the beginning of kindergarten. It's time for schools to help them get there. Perhaps, then, the next Steve Jobs will find school more useful.

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems

Learning Ally and Robert Langston Partner for Dyslexia

One on One with Robert Langston

What’s powering Robert Langston’s dyslexic thinking lately? Following our review of his book, The Power of Dyslexic Thinking: How a Learning DisAbility Shaped Six Successful Careers,we engaged him in an exclusive interview to get a “direct read.”

RFB&D: How did readers respond to your second book? Any key learnings to share?

Robert Langston: The book was really well-received, by both the learning-differences and general dyslexia communities, as well as by other CEOs.

People are still looking for inspiration – reassurance that, “if my child is struggling right now, it’ll still be okay.” In hearing their stories, I felt like I was the one being motivated, not the motivator, which is what others usually look to me for. It really wasn’t about me, or for me, so much as the people I was around, and our shared experiences. At the International Dyslexia Association national conference, there was a line around the booth to get the book – it sold out, and they had to place a second order after the fact.

Most of my followers are Moms. For them, these are intensely personal issues. They feel a tremendous need to help their children experience success and preserve their kids’ self-esteem as they persevere through today’s educational system. Their greatest desire is to see their kids ultimately be able to provide for themselves and their families. Their greatest fear is to see their kids on the wrong side of that upside-down bell curve I describe in my book.

Based on what you’ve experienced since the second book came out, what do you see as the possible subject of your next book?

My second book pretty much touched upon what I was experiencing and learning over the past 15 years – from my time in college [University of West Georgia, despite being functionally illiterate] to now. I continue to come across studies examining whether dyslexia is a gift for every dyslexic, or are a subset of dyslexics gifted, and thus more adept at using compensatory strategies to overcome dyslexic challenges.

The findings in my book came mostly through experientially learning – anecdotally. I was privileged to have met a whole lot of successful dyslexics. That’s why I continue to follow, with great interest, some studies from major foundations, specifically, those related to dyslexics in business settings, CEO traits – to determine if there are any differences in giftedness, or whether dyslexia is a gift overall.

If we could cure dyslexia, rewiring the brain so that these people don’t get the conceptual ability, would they go for it?

What else?

Well, I did sort of “leave open” a big question near the end of my book[1] about a hypothetical dyslexia “pill”: if we could cure dyslexia, rewiring the brain so that these people don’t get the conceptual ability . . . would they go for it? And there are proponents of both sides. On the one hand, there is a real worry that simply teaching kids the things they need to pass tests in school may not translate to what will bring success in the workforce, and could siphon away many of our best and brightest as well.

On the other hand, many word-renowned researchers feel that we are born the way we are, to be able to benefit from early intervention[2] – an additive, not a subtractive process that could bring out even more of the giftedness that is sometimes missed in compensating for dyslexia. “Which came first?”

And so how do your first two books set the stage for what may be your next book?

My first book, “For the Children: Redefining Success in School and Success in Life,” was about my Mom and me; the second book was about other people who influenced me. My next book, which is probably about three to five years away, will likely test out the above theories in full, and will also be about the “fourth generation” of my relatives that have been dyslexic. My grandfather, Alonza Smoot Langston (Big Smoot), was the only child of five without a bachelor’s degree. The education system of the time told my father, Alonza Smoot Jr. (Smoot) that he was “mirror-eyed” – and now he is director of development for Georgia National Produce.

From third grade onward, it’s more about ‘reading to learn’ than ‘learning to read.’

My five-year-old son has LD issues – in fact, he already has an Individual Education Plan – and is presenting all of the classic signs, just like me. My daughter, seven years old, is, like my wife, extremely book-smart. Grades K-3 are a critical time, so my wife and I want to make a proper intervention within the school system, Child Find, and so on. While my wife’s first reaction was “wait and see,” now she is all for proactive intervention. Typically it’s best not to wait, and to accept the help that is available. From third grade onward, it’s more about “reading to learn” than “learning to read.”

What was the question you were asked the most after the second book came out?

It was about the decoding process [i.e., the process by which a word is broken into individual phonemes and recognized based on those phonemes]: what it is, and how to get “affordably good” tutoring assistance.

Like many of these parents, I am familiar with exceptional schools in my general area – in my case, Atlanta, Georgia, offers The Schenck School, Atlanta Speech School, the Galloway School, and others – but also like many of these parents’ situations, these schools are at least a 90 minute-drive away. Like any parent, I want what’s best for my child, without having to pull up stakes and move (although the nationally ranked school system in Oconee County, Georgia is one of the reasons why we moved to this area). The question then becomes, do you pick a school system based on overall test scores, or on whether it is great for every child? (i.e., those with learning differences)

And I know, from these discussions with parents that this issue of where to find affordable tutoring is not limited to Georgia. In the book, for example, I mention the Newgrange School near RFB&D in Princeton, N.J., which has students bussed in from all over the state. During my March 4 appearance on a local morning show, “Good Day Atlanta,” “How do I find a tutor in my area?” was a major concern that I heard.

It can literally be as simple as parents sharing the positive, proven things that work.

The IDA Provider Directory is one place to look; Orton-Gillingham is another potential resource. Parents can also keep an eye out for free seminars in their area that explain IEPs and the legal rights of students with disabilities.[3] According to Charles Schwab, founder, chairman and CEO of Charles Schwab Corporation, it can literally be as simple as parents sharing the positive, proven things that work.

And also like many of these parents, I simply want to make the best decision for my son today – to get him what he needs so he can at least stay on the reading level for his grade. His conceptual skills are presenting, just like mine did: his facility with video games, puzzles, and driving his electric vehicles all show his grasp of concepts not anchored to the written word.

And of course I want my son to not have to suffer like I did – even those I was so blessed to have the perspective and advocacy of two family generations in navigating me through the educational-system maze . . . as well as the opportunity to share a platform with leading lights of dyslexia research like the Shaywitzes. I continue to look into research related to use of accommodations, and whether interventions actually work.

So far, my overall experience has been very positive – with the understanding that, because of who I am, my experience won’t be the same as everyone else’s.

No matter who you are, however, the goal remains the same: what will make a difference for these kids.

[1] pp. 84-85; pp. 116-117; pp. 121-122

[2] e.g., demonstration of plasticity in the neural systems for reading and their ability to reorganize in response to an effective, evidence-based intervention; see: http://dyslexia.yale.edu/About_ShaywitzBios.html

[3] Example: In New Jersey, one such resource is practicing attorney, published author on education law, and parent of a special needs child Ralph Gerstein.

– Doug Sprei

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems

New Dyslexia Documentary Explains Entrepreneur Link

New Dyslexia Documentary Explains Entrepreneur Link

Posted by: Nick Leiber on May 12, 2011

inShare

88More

In 2007, Julie Logan, a professor of entrepreneurship at Cass Business School in London, released the results of a study of 102 entrepreneurs in the U.S. showing that 35 percent identified themselves as dyslexic. This is strikingly high when compared with a national incidence rate of 10 percent in the general population.

Among Logan’s findings: “dyslexic entrepreneurs were more likely to own several companies and to grow their companies more quickly than those who were not dyslexic. They employed more staff and reported an increased ability to delegate. Non-dyslexic entrepreneurs stayed with their companies for longer, suggesting they were able to cope with growth and the accompanying structure that is implemented. In contrast, dyslexic entrepreneurs seem to prefer the early stages of business start-up when they are able to control their environment.”

As Businessweek.com reported at the time:

The broader implication, [Logan] says, is that many of the coping skills dyslexics learn in their formative years become best practices for the successful entrepreneur. A child who chronically fails standardized tests must become comfortable with failure. Being a slow reader forces you to extract only vital information, so that you’re constantly getting right to the point. Dyslexics are also forced to trust and rely on others to get things done—an essential skill for anyone working to build a business.

Now HBO2 is airing Journey into Dyslexia, a new documentary by Oscar-winning filmmakers Alan and Susan Raymond that profiles dyslexic individuals from different fields and backgrounds. One subject is entrepreneur Steve Walker, founder of biofuels manufacturer New England Wood Pellet in Jaffrey, N.H. While the film’s goal is to examine misperceptions and implications of dyslexia inside and outside the business world, the husband-and-wife team say entrepreneurs deserve their own film.

Aware that many entrepreneurs view their dyslexia as a gift, the Raymonds say they were struck by the stories of how founders had discovered their strengths early in their lives, while struggling in school. “Carl Schramm [the CEO of the Kauffman Foundation, who is interviewed in the film] says there’s no particular reason to think that you could connect the dots between a learning disability and entrepreneurs. He believes it’s because they are visionary and they do have an ability to see things other people don’t. They’re people who don’t fit in typical societal norms, so they sort of create their own world. It’s a fascinating idea,” says Alan.

So far the biggest response to the documentary, which debuted last night, has been from entrepreneurs. “It’s three times higher from [them],” says Susan. It airs again on HBO2 on May 14 and May 22, and is on demand through June 5. More studies are on the Raymonds’ website.

Why Dyslexics Make Great Entrepreneurs

The ability to grasp the big picture, persistence, and creativity are a few of the entrepreneurial traits of many dyslexics. Just ask Charles Schwab

When Alan Meckler, the CEO of IT and online imagery hub Jupitermedia (JUPM), was accepted to Columbia University in 1965, the dean's office told him he had some of the lowest college boards of any student ever admitted. "I got a 405 or 410 in English," he recalls. "In those days you got a 400 just for putting your name down! Yet I was on the dean's list every year I was there, and I won a prize for having the best essay in American history my senior year."

It wasn't until years later, at age 58, that Meckler learned he was dyslexic. He struggles with walking and driving directions, and interpreting charts and graphs. He prefers to listen to someone explain a problem to him, rather than sit down and read 20 pages describing it. As a youth, Meckler discovered a unique strength—baseball—and cultivated it religiously to compensate for weakness in other areas.

ASSET OR HANDICAP?

All of these things, according to Dr. Sally Shaywitz, a professor of learning development at Yale University, are classic signs of dyslexia. Shaywitz has long argued that dyslexia should be evaluated as an asset, not just a handicap. She recently co-founded the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, dedicated to studying the link between the two. "I want people to wish they were dyslexic," she says. "There are many positive attributes that can't be taught that people are generally not aware of. We always write about how we're losing human capital—dyslexics are not able to achieve their potential because they've had to go around the system."

It's not clear whether dyslexics develop their special talents by learning to negotiate their disability or whether such skills are the genetic inheritance of being dyslexic. It's a question Shaywitz plans to explore, along with trying to change the way dyslexia is viewed in the educational system and the business world. One project at the center will be an education series to train executives to recognize outside-the-box thinkers who don't perform well on standardized tests.

Shaywitz recently tested a well-known CEO (whom she declined to identify) for dyslexia. The man confessed that he'd hired an outside company to help identify future leaders within the organization by administering a reading test. "'The irony is,' I told him, 'you're eliminating and sifting out all the people like yourself who might actually be the ones to be creative and make a difference.'"

COPING SKILLS

That kind of rejection, along with a penchant for creativity, may help explain why so many dyslexics are inclined to become entrepreneurs. Julie Logan, a professor of entrepreneurship at Cass Business School in London, believes strongly in the connection.

In a study to be published in January, Logan found that 35% of entrepreneurs in the U.S. show signs of dyslexia, compared to 20% in Britain. Logan attributes the gap to a more flexible education system in the U.S., vs. rigid tracking in British schools, and better identification and remediation methods. "Most of the people in our study talked about the role of the mentor and how important that had been," Logan says. "The difference seems to be somebody who believes in you in school."

The broader implication, she says, is that many of the coping skills dyslexics learn in their formative years become best practices for the successful entrepreneur. A child who chronically fails standardized tests must become comfortable with failure. Being a slow reader forces you to extract only vital information, so that you're constantly getting right to the point. Dyslexics are also forced to trust and rely on others to get things done—an essential skill for anyone working to build a business.

"People really struggle to delegate, and these people have learned to do that already," she says. "If you're bogged down in the details, you're not out there looking at where your business needs to go."

LEMONADE FROM LEMONS

Paul Orfalea, who founded the copy-and-graphics chainKinko's 37 years ago, has both dyslexia and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. He proudly attributes much of his business success to an inability to do things most others can. "I would always hire people who didn't have my skills," he says. "My secret was to get out of their way and let them do their job." He is also inured to failure. "You know what's great about a C student? They have risk-reward pretty much well-wired," he says. "A students are always putting in maximum effort, and C students say, 'Well, is it really worth it?'"

Cisco Systems (CSCO) CEO John Chambers says dyslexia helps him step back and see the big picture. His third-grade teacher discovered his reading trouble; he says alternative teaching methods and supportive parents helped him learn to deal with it at an early age. "Dyslexia forces you to look at things in totality and not just as a single chess move. I play out the whole scenario in my mind and then work through it.… All of my life, I've built organizations with a broad perspective in mind."

Meckler, who was one of the first to convert his IT trade publications into a sustainable, ad-supported business model for Web publishing, also strives for the big picture and has little patience for details. "In business meetings…I can hear a whole bunch of people talking about a lot of things, and I seem to be able to cut right to the chase," he says. "I think my mind has been trained…to zero in on the salient point."

FOUNDATIONS FOR SUCCESSFUL DYSLEXICS

Those entrepreneurs who have embraced their dyslexia have also made it their personal mission to pave an easier way for the next generation. Discount brokerage pioneer Charles Schwab (SCHW) started the Charles & Helen Schwab Foundation, a resource center for kids and parents to overcome learning and attention disorders. Orfalea founded the Orfalea Family Foundation, to support and identify different learning styles and try to remove the stigma that comes with them.

Ben Foss, a researcher in assistive technologies in Intel's (INTC) Digital Health Group, started a nonprofit and made a documentary film about the first man in America to win an employee discrimination case based on dyslexia. He's now working to adapt technologies for the blind to also assist people with learning disabilities, too. Despite the titans of business disclosing their dyslexia to the world, Foss says it's still daunting to climb the corporate ladder as a dyslexic. "If you're John Chambers, Charles Schwab, or Richard Branson, sure. But if you're a corporate VP in the mid-ranks, there's a very large disincentive to saying you're dyslexic, because you're still being evaluated," he says. "Ironically, talking about it on your terms is what allows you to become successful."

Of course, being a misfit often lends itself to great entrepreneurship. Health-care entrepreneur and real estate magnate James LeVoy Sorenson has more than 40 medical patents to his name and is responsible for inventing the first computerized heart monitor, the first disposable paper surgical masks, and the first blood-recycling system for trauma and surgical procedures. He also dropped out of community college at 18, and was told by grade-school teachers he was either "slow-witted or developmentally disabled."

At 86, Sorenson says overcoming dyslexia trained him to be persistent and solve problems in new ways: "I like to add one word to the end of many sentences: 'yet.' Instead of saying, 'I can't do it,' I say, 'I can't do it—yet.'"

Coppola is a reporter for BusinessWeek.com in New York .

Source: http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/content/dec2007/db20071212_539295.htm

Is dyslexia inherited?

Dyslexia is inherited, and my family tree is thick with dyslexic branches. My grandfather, father, older brother, and I all have struggled with dyslexia. Does it affect more boys than girls? Current research suggests it affects just as many girls as boys. My family seems to be a bit heavy on the male side, though. That is why I was not surprised when my wife and I started seeing signs that our four-year-old son might be having issues. It was not much, just an occasional "I don't like school" or "School's too hard." With my family history, we decided it would be better to be proactive than reactive.

So, the next day my wife walked into my son's preschool class and asked his teacher if she would meet with us concerning our son. She did not hesitate, and they set the meeting time. Our parental instincts were confirmed the day of the conference when his teacher leaned across the table and said as compassionately as she could, "It does not seem to be sticking." She was referring to his learning of letters and his memory for names. She explained that the letter of the week might be "A." They would work on this letter all week. At the end of the week, she would show him the apple they had used to illustrate the letter. She would ask, "What is this?" Instead of "apple," he would say "tractor." She told us he could describe an apple and could tell her it is something that people eat. He knows what an apple is, but he cannot recall the name of the object or the letter it starts with. Listening to my son's teacher, I was thinking, "This sounds just like me." I took the Woodcock-Johnson-Revised Test of Cognitive Ability at age twenty-three and scored on a kindergarten level in Memory for Names. Also, like my son, I have trouble with the beginning and ending sounds in words. I could tell by the tears swelling in my wife's eyes that she had been hoping that this was one family trait that would die on the vine, but as the reality of the situation set in, the tears became too much, and she had to take a break to compose herself.

I will admit I was a little shocked my wife was not better prepared for this eventuality, since she knew dyslexia runs at least three generations deep in my family, but I do understand that the reality of the moment was overwhelming for her. I also have to admit I was inwardly glad my son was like me. I know how devastating dyslexia can be, and I would be lying if I said I am not a little concerned, but my initial reaction was the same that I have expressed to countless parents who have approached me after my lectures and whispered mournfully, "My child has dyslexia." As they brace for an outpouring of sympathy, they are shocked as I announce in my biggest voice, "GREAT!" This is not the reaction most people expect, but it is how I feel. "GREAT!" I hope my son's mind is naturally wired with the same visual, spatial, conceptual, and intuitive gifts as mine.

Now, with all this said, my son may not have dyslexia like I do. In my opinion, it is too early to diagnose him with an "impaired ability to understand written language: a learning disorder marked by a severe difficulty in recognizing and understanding written language, leading to spelling and writing problems," as defined by Encarta ® World English Dictionary. Even so, my wife and I want to make sure our son has all the advantages available today, just in case the acorn has not fallen far from the tree.

At the end of our conference, the teacher indicated she would like to start the process to evaluate our son. I served on the State Advisory Panel for Special Education in Georgia for seven years, so I know she is asking to initiate the national Child Find process. Child Find is a continuous process of public awareness activities, screening, and evaluation designed to locate, identify, and refer, as early as possible, young children with disabilities and their families who are in need of Early Intervention Programs (EIP). She did a great job explaining that in our county there is a representative from the local public school system whom she could contact on our behalf to evaluate our son for initial signs of learning difficulties. First steps are basic: hearing and vision screenings to rule out problems in those areas, a parental questionnaire, and observation of the student in the classroom. The Child Find process is important in case an Individual Education Plan (IEP) is needed in the future.

Studies show that parents wait an average of twelve to eighteen months to act on their initial instinct that something might be wrong. The best advice I can give is don't wait; listen to your instinct, be proactive not reactive, and accept the help that is available.

My family has been on its journey with dyslexia for generations, and it will be interesting to see if my son sprouts as a new branch of this tree. I rejoice in the possibility that my son may have the power of dyslexic thinking within him and be gifted with a visual, spatial, conceptual, and intuitive brain. But at the same time, I hope we have come far enough that I can prune out some of the more painful limbs that have plagued the Langston men in the past, allowing him to grow even stronger than those that have come before him.

Wish us luck,

Rob

"Good timber does not grow with ease; the stronger the wind, the stronger the trees,"

-- Author unknown.

Source: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/power-dyslexic-thinking/201001/is-dyslexia-inherited

Welcome to the Age of Dyslexia Awareness

On Wednesday, February 17, I was a guest on the blog talk radio show Midlife Matters with Les Brown. you can click on the blog talk microphone image (left) to hear the interview. The conversation Les and I had started me thinking about the global state of dyslexia. During the interview, I expressed this theory.

We are in phase two of a three-phase process necessary to eradicate dyslexia as a fundamental learning disability in our society. Phase one is what I am calling "The Age of Ignorance," phase two is the "The Age of Awareness," and phase three will be the "The Age of Consciousness."

The Age of Ignorance

Unfortunately, my father, grandfather, and the generations of dyslexics before them were born in the Age of Ignorance. Seeds for a language-based, multisensory, structured, sequential, cumulative approach to teaching reading were being sewn in the early 20th century by pioneers such as neuropsychiatrist Samuel Torrey Orton and psychologist Anna Gillingham, but the world as it pertained to dyslexics was still overwhelmingly dark. During this age of darkness, terms such as retarded, slow, lazy, and even mirror-eyed (referring to turning letters and words around on the page) were used to describe individuals with dyslexia. Misunderstanding ran rampant, and seemingly unbreakablestereotypes were born, such as "dyslexics read backwards." My heart goes out to the generations of dyslexics who suffered through these dark times.

The Age of Awareness

I consider myself extremely lucky to have been born at the beginning of the Age of Awareness. This is a time when dyslexics themselves have decided to walk into the light and not be shamed by their dyslexic way of thinking. Standing on the shoulders of dyslexic giants such as Charles Schwab, Paul Orfalea, Richard Branson, Henry Winkler, Diane Swonk, Whoopi Goldberg, Jewel, and many others who have lent some portion of their time, resources, or fame to the cause of global dyslexia awareness, it is my belief that a wave of awareness has been started.

Embracing this era of scientific discovery enveloping dyslexia, I believe this age will be expedited just as so many other modern phenomenons have been accelerated by technology. The science behind how dyslexics process the written language and moreover the world is here and now. Quantum leaps are being made in our current era, propelling us into an undeniable understanding of the power of dyslexic thinking.

MEG scans, fMRI technology, longitudinal studies, and research-based multisensory approaches to early childhood interventions are being entertained daily by people "within the know" who are financially or geographically able to take advantage of the modern age of dyslexia. Seeds have been sewn, and fruit is coming to bear, but the challenge of this age will be feeding the masses.

The Age of Consciousness

The third age will come when a shift in consciousness is felt around the world, with the realization that there is a better way, when the human race collectively realizes the systemic benefit of changing an antiquated system of education. Education will become a catalyst for change, and scientific certainty will promote better ways to teach.

I can feel the pain necessary for change building each time a teacher shares the heartbreak of watching another child fall behind. I hear the pain in the voices of parents desperately calling for help in a system that does not support their child's learning needs, and I see it in the eyes of our children being warehoused in juvenile detention centers, as half of them are functionally illiterate

What will be the benefits of this process of change? The visual, spatial, conceptual, and intuitive mind of the dyslexic will benefit. Teachers will succeed in a more holistic approach to meet their dyslexic students' educational needs, a free appropriate public education will be scientifically derived from a research-based multisensory learning environment, parents previously on a mission to litigiously tear down school systems for their inept attempts to meet their children's educational needs will pour their resources into supporting local schools, and last, there will be a reallocation of dollars being freed by a decreasing demand for beds in our juvenile detention facilities because our children are being caught before they fall through the cracks. All this will be brought on by a shift in global consciousness surrounding dyslexia.

There is a better way. Losing so many of our best and brightest is no longer acceptable, and their contributions to our society are worth the effort involved in changing a broken system.

At middle age, I find myself in the middle age of dyslexia.

Here's to a brighter future,

Rob