The Paradox of Dyslexia: Slow Reading, Fast Thinking

MOLLY PATTERSON APRIL 3, 2011 2

Dr. Sally Shaywitz is the Audrey G. Ratner Professor in Learning Development, and Dr. Bennett Shaywitz is the Charles and Helen Schwab Professor in Dyslexia and Learning Development and Chief of Child Neurology at Yale University. Together they head The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, which studies the correlation between reading and IQ in dyslexic and typical students, shedding new light on what has been termed “the hidden disability.”

Dyslexic students are often frustrated or confused as to why certain assignments – reading, for example – take them longer to complete than their peers. “Someone once said to me, ‘I wonder what it feels like when a child first realizes that he or she can’t do what those around him or her are doing.’ And that was really quite devastating,” says Sally Shaywitz.

She and her husband Bennett set out to help these students by examining the science of dyslexia. Most recently, the Shaywitzes at the Yale Center for Creativity & Dyslexia have established a connection between IQ and reading in dyslexic students versus typical students.

Connecting IQ, Cognition, and Behavior

The Shaywitzes conducted epidemiologic longitudinal research on a large sample population of Connecticut students. Twenty-four elementary schools were chosen from the state of Connecticut – two were randomly selected from twelve separate towns across the state – and students were tested upon entry into kindergarten. The same students were tracked over more than twenty years, each taking a reading test annually and an IQ test biannually until adolescence. The tests were individually administered, constituting a statistical “gold standard,” according to Sally Shaywitz. Including these tests, researchers examined the cognition and behavior of dyslexic versus typical students and then recorded and compared the brain images of dyslexic and typical students.

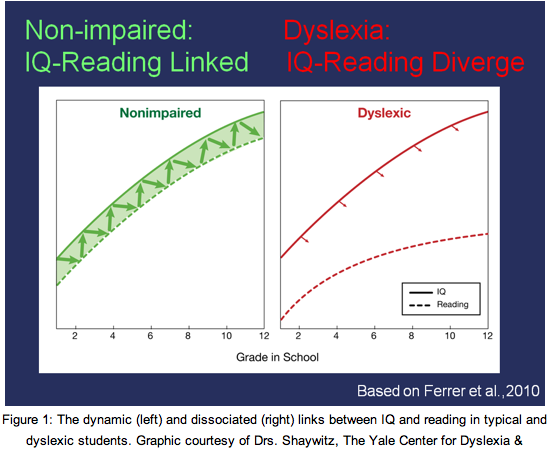

The results show that in typical readers, IQ and reading track together and are dynamically linked over time. Sally Shaywitz calls the two components “kissing cousins” because they are “intertwined,” a conclusion that she notes has been widely accepted by the public. In contrast, the Shaywitzes found that in dyslexic readers, IQ and reading diverge. Thus, a highly intelligent dyslexic student can have a low reading score. This paradox is illustrated in Figure 1, where the left panel shows the dynamic link between reading and IQ development in typical readers, and the right panel shows the disconnection between reading and IQ in dyslexic readers.

figure 1

Figure 1: The dynamic (left) and dissociated (right) links between IQ and reading in typical and dyslexic students. Graphic courtesy of Drs. Shaywitz, The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

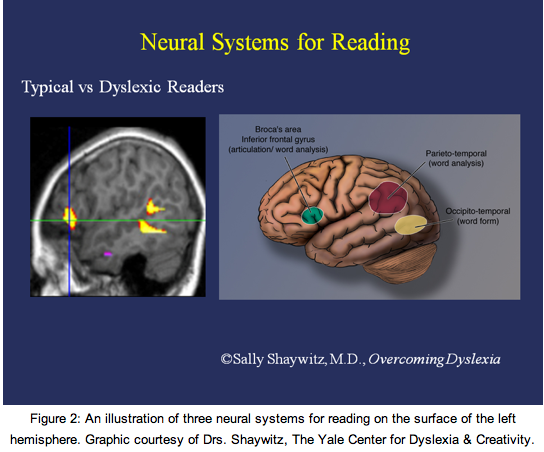

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to record images of dyslexic and typical children and adoslecents. Figure 2 illustrates these images: The left figure is a composite fMRI of 74 typical readers contrasted with 70 dyslexic readers. The yellow regions are parts of the brain that are more active in typical readers com-pared to dyslexic readers. The right figure is a schematic view. Both images show three systems for reading: an anterior system in the region of the inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area), which is believed to serve articulation and word analysis, and two posterior systems, one in the parietotemporal region, which is believed to serve word analysis, and a second in the occipitotemporal region (the word-form area), which is believed to enable the rapid, automatic, fluent identification of words. These systems are used for fast, fluent automatic reading, but the scans show that dyslexic individuals are neurobiologically wired to read slowly.

figure 2

Figure 2: An illustration of three neural systems for reading on the surface of the left hemisphere. Graphic courtesy of Drs. Shaywitz, The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

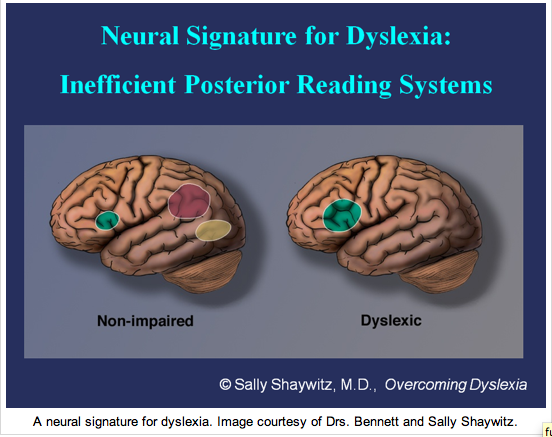

Functional brain imaging has made the once-hidden disability of dyslexia a visible one, increasing awareness and understanding of dyslexia in education and policy-making. As one of many resulting policies in education, dyslexic students are often allotted additional testing time. This allows them to demonstrate what they know and not be penalized for slow reading that is biologically determined and therefore beyond their control. These compelling findings of a neural signature for dyslexia are, according to Bennett Shaywitz, “replicable around the world.”

Dyslexia Around the World

Dyslexia, a fundamental difficulty in separating the sounds of a spoken language, is common to every alphabetic and logographic language. In languages with increased transparency between sounds and letters, including Italian or Finnish, dyslexic children may initially appear to read accurately, with difficulties often not emerging until adolescence or young adulthood. Bennett Shaywitz cites a study by Eraldo Paulesu, who aimed to compare dyslexia in Italian, English, and French college students. He had to recruit Italian college students in schools of engineering because so few Italians had been diagnosed with dyslexia. Indeed, dyslexics not only succeed in engineering but in a range of fields including medicine and law. Ultimately, although they are slower readers, dyslexic students have strengths in higher order thinking and reasoning skills. In fact, as Bennett Shaywitz points out, the 2009 Nobel Laureate in medicine, molecular biologist Dr. Carol Greider, is dyslexic.

The scientific and educational communities have reacted positively to the results of the IQ and reading study, says Sally Shaywitz. The results are particularly compelling because they confirm the relationship between IQ and reading, elucidate the experiences of the dyslexic, and corroborate the clinical findings of other researchers.

As a secondary result of the study, the data identified certain basics of dyslexia that were initially unknown or misunderstood. “From an epidemiologic perspective, we’ve been able to determine from the random sample of Connecticut school children that dyslexia affects one in five individuals,” says Sally Shaywitz. “We’ve also found that there is no significant difference between the number of girls and boys identified [as having dyslexia].”

figure 3

A neural signature for dyslexia. Image courtesy of Drs. Bennett and Sally Shaywitz.

Identifying Dyslexia in School Systems

School systems often have trouble identifying dyslexic students because testing students for dyslexia is not a standard procedure, and dyslexic individuals often exhibit only subtle symptoms. It is often difficult for teachers to recognize that the same child who is extremely bright can also be the one who is struggling to retrieve spoken words or to read fluently.

To better help students with dyslexia, Sally Shaywitz suggests teachers instruct dyslexic students in smaller groups of a size no bigger than five students. Instruction needs to be delivered in this manner consistently – 60 to 90 minutes a day, 4 to 5 days a week – by educators trained in teaching dyslexic students. This is a tall order and “a very slow, laborious process,” Sally Shaywitz concedes, but rewarding in the end. Sally Shaywitz says that accuracy can be taught; however, closing the gap in reading fluency continues to remain an elusive goal.

Looking Ahead: Standardized Testing

The Shaywitzes are focuing new research on how the disparity between IQ and reading in dyslexics affects their performance on high-stakes exams such as the SAT, MCAT, and other standardized tests. Dyslexic students require the accommodation of extra time, which is supported both by scientific evidence and the law; but testing agencies often withhold this accommodation “to the detriment of the student and society,” says Sally Shaywitz. The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity has focused its efforts on determining the “predictive validity” of these tests. Such results may be uneven between dyslexic and typical students, given the heavy emphasis of reading fluency on standardized exams. The data on this new research is not yet available, but will certainly be anticipated by students, educators, and testing companies alike.

About the Author

MOLLY PATTERSON is a sophomore Chemical Engineering major in Trumbull College.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Drs. Sally and Bennett Shaywitz for their time and for their dedication to research.

Further Reading

Ferrer, E., Shaywitz, B.A., Holahan, J.M., Marchione, K., and Shaywitz, S.E. Uncoupling of Reading and IQ Over Time: Empirical Evidence for a Definition of Dyslexia. Psychological Science, 21(1) 93–101, 2010.

Shaywitz, S. Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. 2003. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Bennett A. Shaywitz, Pawel Skudlarski, John M. Holahan, Karen E. Marchione, R. Todd Constable, Robert K. Fulbright, Daniel Zelterman, Cheryl Lacadie and Sally E. Shaywitz, “Age-Related Changes in Reading Systems of Dyslexic Children,” Annals of Neurology, Volume 61, Number 4, (2007): 363 – 370.

Sally E. Shaywitz, Maria Mody and Bennett A. Shaywitz, “Neural Mechanisms in Dyslexia,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Volume 15, Number 6, (2006): 278-281.

Topics:

dyslexia resources for parents, dyslexia resources for teachers, dyslexia resources for students, dyslexia resources for educators

Dyslexia organizations, Orton gillingham, international dyslexia association, ldonline, national center for learning disabilities, ncld, council for exceptional children, cec, learning disability association, lda, yale center for dyslexia

Dyslexia topics, signs of dyslexia, early reading problems